Introduction

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the Pre-Raphaelite movement generated a large amount of art and literature that remains much-loved and influential over a century later, even though at the time of production it often met with criticism and disapproval. Investigating the public and private dynamics between certain main players in the movement, as well as analyzing their treatment of female subjects in both Classical and Renaissance-era idioms and styles, sheds light on the sources of their inspiration and creativity and the complex relationship between real life and art.

Dramatis Personae

John Ruskin (1819-1900)

The earliest days of Victorian Pre-Raphaelitism – really almost an embryonic period – can be traced back to the early 1840s with John Ruskin, who became the most important art critic in the English-speaking world. He wanted to take a “romantic, scientific, and anti-classical” approach to art, with an emphasis on naturalism and landscaping in conjunction with weather effects and man-made architecture.[i] This approach was a reaction to the heavy stylistic idealization of Neoclassical art, which had been extremely popular during the 18th Century. Ruskin promoted Gothic architecture in his book The Stones of Venice (1851-53), and his love of medieval art influenced the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. He praised their “truth to nature” approach in the pamphlet Pre-Raphaelitism (1851).[ii]

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882)

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti was the son of Neapolitan poet, scholar, and émigré Gabriele Rossetti. Gabriele was exiled from Naples in 1824 because of his revolutionary politics, when he escaped to England and supported himself as a teacher of Italian as well as writing commentaries on Dante Alighieri, eventually becoming a professor at King’s College in London.[iii] Two years later he married half-Italian Frances Polidori, sister to John, Lord Byron’s physician and friend. Together they had four children, three of whom went on to be heavily involved in the Pre-Raphaelite Movement. William Michael was among the original members of the Brotherhood, and edited their magazine; Christina was an artist and poet who contributed to the magazine but was never officially considered part of the Brotherhood.

Gabriel Charles Dante exhibited a talent for art from an early age. Like his siblings, he was multilingual, and read a lot of contemporary poetry as well as classic literature such as Shakespeare and the Bible.[iv] While Ruskin was writing about nature and art (the first volume of his Modern Painters was published in 1843), Sass’s Drawing Academy in Bloomsbury[v] was preparing Rossetti, as a young teenage student, to attend the Royal Academy of Art. This was to secure his future as an artist and enable him to learn from masters as well as provide a channel for him to exhibit his work.

John Everett Millais (1829-1896)

John Everett Millais was born into a rich family in Southampton in 1829. His father was a wealthy gentleman from the Channel Islands; his mother, the daughter of an affluent saddler.[vi] Millais had passed through Sass’s much faster than Rossetti, and was enrolled on probation at the Royal Academy in 1840 at the age of eleven after only a year’s preparatory schooling.[vii] He had also won a silver medal at the Society of Arts when he was just nine years old.[viii] The talent and youth of both Rossetti and Millais were perhaps equally remarkable; it is probable that had Rossetti and Millais been born in the 21st century, they might have been known first as gifted children, and later as that deliciously powerful word, multipotentialites. Art and poetry were their main focus, but later the movement with which they became inextricably linked would embrace a large variety of art forms.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB)

The story of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood truly began in 1848, when the Royal Academy opened an exhibition including a work by William Holman Hunt based on Keats, whose writing Rossetti admired particularly. Rossetti, on attending the exhibition, was impressed only by Hunt’s painting and none of the others displayed, as a result of which he struck up a friendship with Hunt. Millais and Hunt were at this point already friends, and all three met together to talk about art and poetry.[ix]

Hunt had studied Ruskin’s philosophy on art, and this undoubtedly influenced the discussions. Their conclusion was simple yet radical: starting with Raphael’s Transfiguration in 1520, artists had left behind the ‘simplicity of truth’ showcased in earlier Renaissance art, and it was up to their small group to bring art back to its former naturalistic glory.[x]

The group gradually became more consolidated over the next few years, bringing in more members, and establishing itself as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. They even had their own list of heroes, called the ‘Immortals’: revered religio-historical figures ranging from Jesus and Shakespeare to Keats and King Alfred.[xi] In January 1850 they published the first issue of their magazine, The Germ, which was Rossetti’s brainchild. Various members and satellites of the Brotherhood contributed to the first issue, including Rossetti’s brother William Michael, their sister Christina, and Ford Madox Brown. It also marked the first appearance of Rossetti’s poetry in print.[xii]

The complexity of the interpersonal relationships between those involved with the Brotherhood began to manifest itself quite early on. Millais became Ruskin’s protégé in 1851, but this led to a scandalous development – Millais turned out to be not merely painting Ruskin’s wife Effie, but also falling in love with her. The marriage was annulled and Effie married Millais in 1855.[xiii] Ruskin thereafter withdrew his support from the Brotherhood, and this as well as growing tensions between its members led to its dissolution only four years after it was initiated. However, the individual artists continued to work and create, and this artistic movement outlasted the initial Brotherhood by several decades.

Lizzie Siddall

It was during this early period that the Brotherhood began developing complicated relationships with women they called ‘stunners’. It is important here to note that this categorization does not always refer to traditional or fashionable standards of beauty; rather, the ‘stunners’ were sometimes attractive because they were unusual and striking in appearance.[xiv] The first was Lizzie Siddall, discovered (according to several accounts, at least) in a milliner’s shop in 1850 by Walter Deverell while he was shopping with his mother. A stately, ‘lady-like’ red-head, she was not conventionally pretty, but she caught the fancy of the Brotherhood’s naturalistic painters and quickly became a favourite working model.[xv] As with Millais and Effie Ruskin, though, the boundary between artistic appreciation and romantic intimacy became blurred once Lizzie and Rossetti began to develop feelings for each other. Hilton describes Rossetti as “tak[ing] possession of her […] guard[ing] her jealously.”[xvi] Their relationship was secret for some time, under the guise of modelling, and then later tutelage, as Lizzie was becoming an artist in her own right. Rossetti dragged his feet about marrying her mainly due to his own financial constraints, but the secretive nature of the relationship appears to have been Lizzie’s wish at least in part.[xvii] They did eventually become engaged, but broke it off in 1858, only to be married at last in 1860. Lizzie’s health had been bad for some time and she had become addicted to laudanum; Rossetti believed her to be dying, which appeared to be the final push he needed to legalize their relationship.[xviii] After giving birth to a stillborn child the next year, Lizzie’s health declined sharply, in inverse proportion to her drug dependency, and she died of an overdose in 1862.[xix]

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898)

Born in Birmingham in 1833, Edward Coley Burne-Jones was possessed of a powerful and poetic imagination which he relied upon throughout his youth. He loved Classical mythology as well as Gothic literature and the Romantic poets, particularly Keats and Coleridge.[xx] At Exeter College in Oxford in 1852 he met William Morris, a lad from a Welsh family living in Walthamstow, and they became fast friends due to their common interests in poetry and the past, as well as their shared heritage. Burne-Jones did not even seriously focus on painting until he was twenty-one; then in 1855 he came across Rossetti’s work, and became his protégé soon afterward.[xxi]

In 1860 Burne-Jones married Georgiana Macdonald, the daughter of a Nonconformist minister whose family he had known in Birmingham. He was prone to depressive episodes, and still inclined to take refuge from the world in his imagination. Burne-Jones was also not satisfied in his relationship with his wife, who could not hope to live up to the romantic ideals created in his own head by his love of the poetic and mysterious. She was a woman of intelligence and loyalty, with strong political opinions, but did not handle pregnancy and childbirth well, as she was not physically strong.[xxii] In 1868 he had an affair with a married woman, Maria Zambaco, the daughter of an extremely wealthy and well-connected Anglo-Greek merchant family. Her marriage had failed, possibly in part due to the unpleasant nature of her husband, a doctor of venereal disease who was accused in-house of being involved with child pornography.[xxiii] Maria’s relationship with Burne-Jones was tempestuous and ended with her attempted suicide in which the police became involved, scandalously.[xxiv] This was just the first in a series of affairs, which, unsurprisingly, led to a cooling of intimacy between Burne-Jones and Georgiana, although she stayed with him and apparently loved and forgave him.[xxv] In his biography, which she wrote, she speaks of him with affection, though she also has a great deal of warmth to spare for Morris, with whom she enjoyed a long and close friendship.[xxvi]

Burne-Jones maintained his boyhood friendship with Morris through his life, and involved himself in Morris’ design company, “The Firm” (Morris, Marshall, Faulkner, & Co).

Jane Burden

In the autumn of 1857, eighteen-year old Jane Burden went to the theatre with her younger sister Bessie, where she caught the attention of Rossetti, who was also attending. Like Lizzie, she was not conventionally beautiful. William Morris, who was also smitten with Jane, described her in the poem Praise of My Lady as made “of ivory” with cheeks “hollow’d a little mournfully” and “thick and crisped” hair “dark, but dead as though it had/ Been forged by God most wonderfully/ Of some strange metal, thread by thread.”[xxvii] This pale, brooding kind of beauty was a far cry from the golden hair and small features held in such high regard by Victorian society.[xxviii] But Rossetti was fascinated by her, and his personality was such that it was hard for anyone to argue with his visions. In fact she became known as a ‘stunner’ and her looks “later became a standard of feminine appeal evolving […] into the sultry and enigmatic Hollywood star.”[xxix]

Also like Lizzie, Jane belonged to a lower economic class than the painters whose muse she became; she was the daughter of an illiterate stablehand, who did not have the same social advantages and therefore could not expect a great deal in the way of prospects for her future.[xxx] William Morris, however, fell in love with her, and after courting her with poetry and a painting (Queen Guenevere, 1858) proposed marriage. They were married in 1859, and Jane’s quality of life improved dramatically, since Morris was very well-off. In 1861 they had their first daughter Jane (“Jenny”), followed by their second, Mary (“May’), in 1862.

Jane’s explanations for her actions were ambiguous, but it seems likely that she was never truly enamoured with Morris despite remaining married to him for thirty-seven years, and may have accepted him partly in order to raise her own status and partly to remain in Rossetti’s vicinity as a satellite and model of the Pre-Raphaelites.[xxxi]

Rossetti and Jane embarked on a long and passionate love affair sometime in the 1860s after Lizzie’s death. Morris, always an object of friendly ridicule from his colleagues due to his short stature and curly hair, had to swallow the indignity of Rossetti’s designs on his wife. At the same time Morris was subjected to more and more unkindness in the form of nicknames and caricatures, such as The Wombat (1869) in which Rossetti portrays him as a woolly, squat wombat held by Jane on a leash (see Fig. 1).[xxxii]

“The Bright Web She Can Weave” – Rossetti’s femmes fatales

Although Rossetti became best-known for his erotically-charged images of women, he began by painting traditional Christian subjects. His first publicly displayed work was The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849), which was seen at a free exhibition in Hyde Park Corner that year.[xxxiii] This painting is unusual in its manner of approaching Mary and her family – mundane attire and activities such as embroidering and gardening are shown, in a departure from more traditional scene-setting and iconography of the Holy Family – but it gives no real suggestion of Rossetti’s later style of painting brooding, dangerous femmes fatales.

In Ecce Ancilla Domini/The Annunciation (1850) Rossetti further develops his individualistic interpretation of religious imagery. His Virgin Mary is a gloriously uncomfortable red-head woken from her sleep by Gabriel proffering a lily of purity (see Fig. 2). The weird, eerie quality of the scene, with Mary rising from her bed on being approached by the angel, is enhanced by Rossetti’s choice of colour palette, which runs to a base of primary colours (red and blue) and a lot of white. This painting has been described as a “radical reinterpretation of the subject”, as works depicting the Annunciation traditionally represented the Virgin “in studious contemplation […] passively receiving the news.”[xxxiv]

Around the time of his romance with Lizzie in the mid-1850s, Rossetti became obsessed with Dante Alighieri, which was perhaps inevitable given the inclusion of the Florentine poet’s name in his own as well as his poetic bent and family connection – not only was his father a Dante scholar, but there were also similarities between his father’s political exile and that of Dante. Rossetti’s art during this period is heavily influenced by Dante’s works as well as his own feelings for Lizzie. Jan Marsh explains that “far from being the libertine of popular repute, Gabriel was at this date a sentimental and idealistic young man who painted pious and romantic subjects […] Lizzie was to be rescued from her lower-class origins and elevated into a superior world, through art and love. She was to be idealized.”[xxxv] Beata Beatrix (1863) is probably the most striking example of this dual influence (see Fig. 3). It is Rossetti’s symbolic farewell to Lizzie, the Beatrice to his Dante, the muse whose loss both devastates and inspires the poet and artist. As with Dante’s own work, Beata Beatrix contains layers of symbolism – Rossetti places himself in the background of the picture as Dante, who “looks across at Love, portrayed as an angel and holding in her palm the flickering flame of Beatrice’s life.”[xxxvi]

Lady Lilith, however, also painted in 1863, marks a definite break in Rossetti’s choice and portrayal of subjects. Rossetti was beginning his move toward what would become his artistic signature – depictions of powerful women who ensnare men with their beauty and sexual confidence. Lady Lilith deals with the Jewish story of Adam’s first wife, popularized and romanticized by Goethe in Faust Part I (1808).[xxxvii] Rossetti places her combing her ‘enchanted hair’ and staring, Narcissus-like, at her own reflection in a hand-mirror (see Fig. 4).[xxxviii] Rossetti had, quite early in his career, developed an art process that intermingled painting with writing – he usually wrote sonnets or other forms of poetry to accompany his paintings, which provide insights not only into the subject of the picture but also into his intentions when painting. Lady Lilith was no exception. The sonnet discusses Lilith’s personality, an eternally youthful “witch” whose “sweet tongue could deceive” and whose “strangling golden hair” entrapped the hearts of men.[xxxix]

Rossetti later discussed the painting as a depiction of a “Modern Lilith […] gazing on herself in the glass with that self-absorption by whose strange fascination such natures draw others within their own circle.”[xl] Taken in context with Rossetti’s statement, the painting demonstrates quite effectively John Berger’s criticism of the male gaze in art, picturing a woman “because you enjoyed looking at her”, but then “put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman.”[xli]

- S. Lowry, a 20th-century artist who became a collector of Rossetti’s paintings, expressed an interesting insight in his letter to a friend:

“They are not real women … They are dreams … He used them for something in his mind caused by the death of his wife.”[xlii]

Whether or not this psychological angle is true, there was a definite change evident in Rossetti’s work after 1862.

One of his most famous, and most interesting, paintings is Proserpine (1874), modelled by Jane Morris, in which Persephone stares off-centre out of the painting, holding a pomegranate out of which she has taken the bite that will seal her fate and ensure her return to the Underworld every winter (see Fig. 5). In a letter to Turner, Rossetti describes the subject of the painting as the “Empress of Hades”, and speaks of her “enchained to her new empire and destiny”, looking “furtively” at the shaft of light she sees from the world above.[xliii] The symbolism in this piece is breathtakingly heavy – it is Persephone, but it is also Jane, staring out at her future with a brooding, dissatisfied, melancholy expression. A. S. Byatt discusses the feelings this painting evokes in an audience that is aware of the interpersonal context surrounding it:

“There is something appalling, I have discovered, in looking at a whole series of Rossetti’s images, more and more obsessive yet essentially all the same, brooding, dangerous, sexually greedy, too much […] I wondered […] what effect did these images of Rossetti’s feelings have on Morris, as they hung in his house or were bought by others?”[xliv]

Rossetti’s post-1862 seductive figures, mostly modelled by Jane, became as much a part of his distinctive artistic style as his rich use of colour. They also provide a window into his thought process as well as a mirror of his emotions regarding Jane. She is the seductress whose enchantments captivate him, yet at the same time she is Persephone, who cannot escape the destiny marked out for her by her actions.

‘Her Bright Resplendent Beauty had Somewhat in it Divine’ – Burne-Jones and the Fairytale Damsel in Distress

Rossetti and his friend and protégé Burne-Jones had, by the 1860s, effectively taken hold of the original Pre-Raphaelite movement and made it into a new creature with heavy emphasis on poetic and aesthetic Romanticism – “themes of eroticized medievalism (or medievalized eroticism) and pictorial techniques that produced moody atmosphere.”[xlv] But while Rossetti’s focus was most often on the dark and seductive, the Liliths and witch-queens of literature, Burne-Jones portrayed the opposite side of the coin regarding the nature of the feminine in folktales, poetry and mythology, illustrated by his Briar Rose series (1871-1890).

The literary tradition of the ‘damsel in distress’ goes back a very long way in the history of storytelling. To take just one example from the wide variety provided by mythology across the world, the Greek myth of Andromeda and Perseus contains all the necessary ingredients for this type of tale – the beautiful, helpless princess, the monster that threatens her, and the hero who must save her life by showing his strength and ingenuity and slaying the monster.[xlvi] In medieval fairytales the theme of courtly love is often added to this pre-existing trope, where the prince or hero must overcome trials to satisfy his longing for the princess. Charles Perrault in the 1600s had collected some of the most popular folktales in Europe, and translated them into French with his own embellishments, and in the mid-1800s the brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Anderson were re-translating and retelling the stories again to great popularity. By the time of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the Gothic Revival had made even further additions to the tropes of the classic fairytale: the “haunted castle”, the Byronic, malevolent yet intriguing villain, mysterious and often gruesome deaths, “supernatural happenings [and] a damsel in distress” all tied together with “violent emotions of terror, anguish, and love”.[xlvii]

Burne-Jones capitalized on this Victorian revived appreciation for supernatural tales in which the heroine must be rescued from a horrid fate by the dashing hero.

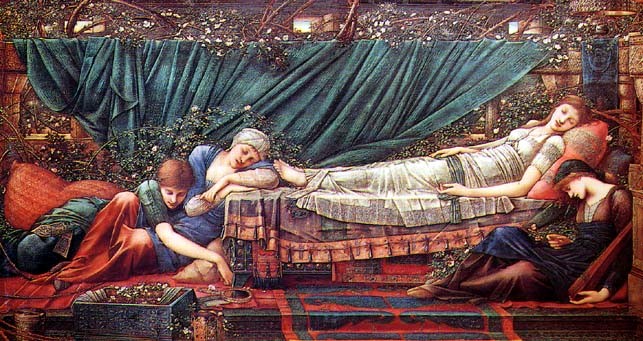

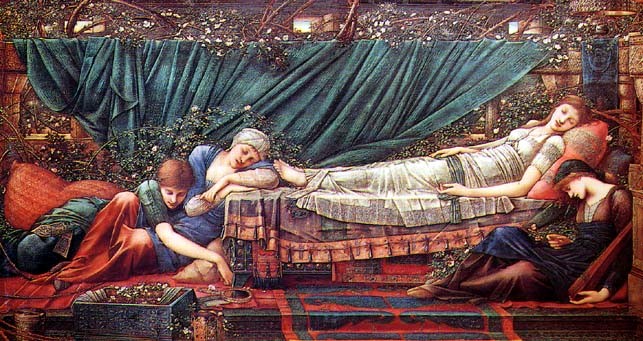

The four Briar Rose paintings show scenes from the Sleeping Beauty fairytale in a progressive sequence as if the viewer is taking on the character of the prince who is destined to break the sleeping curse – first The Briar Wood, where the bodies of defeated princes lie entwined with briar thorns; second The Council Chamber, where the king and all his advisors have slept for a hundred years; third The Garden Court, full of weavers asleep at the loom with the thorny branches climbing over the walls of the castle; finally The Rose Bower, in which the princess is seen prone on her bed with her attendants slumbering on the floor (see Fig. 6).

The story of Briar Rose, the beautiful princess waiting to be awakened and thus rescued by a heroic prince, coincides strangely well with the attitude of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood toward the women they ‘rescued’ from lower-class lifestyles.

The spell in the Sleeping Beauty story is broken with a kiss, the clean-fairytale shorthand for love and sexuality, while the versions published by Perrault and the Brothers Grimm are highly sanitized versions of what was originally a far more shocking folk tale. Similarly, the striking young women found by Rossetti and the others were likewise ‘awakened’ from their previous existence and given new life as models for painting and poetry alike, with a definitely sexual component to this ‘liberation’.

Burne-Jones tended to prefer the more ethereal and sweet aspects of folklore, as opposed to Rossetti’s dark and brooding mythological elements. For Burne-Jones, the medieval ideal of courtly love, the passive heroine who must be rescued, the mystique of magic, seem to be essential romantic components.

However, it is important to note that, as with Rossetti, the influence of individual relationships affected the style and subject matter of some of Burne-Jones’ work. While his main focus was on the damsel in distress of European fairytale, his stormy affair with Maria Zambaco produced works surprisingly similar to some of Rossetti’s paintings. She appears in The Wine of Circe (1869) and The Beguiling of Merlin (1874) – both depicting powerful witches who beguile or entrap otherwise strong men with a combination of magic and feminine wiles.

Conclusion

The paintings of women by Rossetti and Burne-Jones provide an interesting insight into the complicated psychological aspects of their sexual attractions and social lives. The use of literary archetypes in their work connects with their romantic entanglements as well as with their own visions of idealism and romance.

However, caution is advised: the art itself provides only a glimpse into the artists’ view of the world and their relationships. This, along with established suppositions about gender roles in Victorian society, makes it all too easy to see Lizzie, Jane, and the others as victims or at least pawns of the men who seemed to manage their lives. While this may be true to some degree, it is also important to remember that these women were not two-dimensional figures: “They had talent, personality, and ambition and were capable of exerting control over their own destiny.”[xlviii] Lizzie had dreams of becoming an artist, and those dreams were realized to some extent because of her association with Rossetti. He was willing to help her perfect and exhibit her talent in a society where women could not attend the Royal Academy and art should only be a hobby for them. Jane avoided an uncomfortable lower-class life by marrying the wealthy Morris, even if she did not love him, and was still able to conduct an affair with the true object of her affections despite her marriage.

It seems possible that the sometimes confused and inconsistent dichotomy between the two archetypes – femme fatale and damsel in distress – in the Pre-Raphaelites’ work might be a result of their own struggles to reconcile their desires and experiences with the women they painted and loved. Rossetti painted both Beata Beatrix and Proserpine; Burne-Jones painted both Briar Rose and The Beguiling of Merlin. The different loves in their lives seem to coincide with the subjects of their work.

Were the women they loved truly either beautiful, conniving predators determined to ensnare them or sweet, pure fairytale princesses trapped by their circumstances? As in most things, the truth probably lies somewhere in the middle. People rarely fit perfectly into categorization, and archetypes are there to provide a basic understanding of the world, not to restrict human personalities into rigid outlines. The paintings Rossetti and Burne-Jones left behind gift us with the ability to see through their eyes for a brief moment.

The Pre-Raphaelites’ love of natural form, bold colour, and medievalism left a strong impression on the art world. Not everyone enjoyed their work: Dickens famously reacted badly to Millais’ Christ in the House of His Parents (1850), and scathingly pronounced it “mean, odious, repulsive and revolting.”[xlix] However, their art burgeoned into a movement of British and American art with many followers, and its romantic idealism has had a lasting appeal. “Their institutional critique is a crucial piece of the history of modern art in Britain”, because it opened the way for artists to become popular for their individuality and unique vision rather than for their ability to conform to a recognized and accepted format.[l] The Brotherhood’s effort to connect with Pre-Raphaelite Renaissance art was a conscious decision, but the Movement itself can be compared to the Renaissance in its fresh perspective and its strong desire to shed the constraints of tradition and create new trends in the art world.

Appendix

(Fig. 1) http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/s607.rap.html

(Fig. 2) http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/rossetti-ecce-ancilla-domini-the-annunciation-n01210

(Fig. 3) http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/rossetti-beata-beatrix-n01279

(Fig. 4) http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/s205.rap.html

Lilith, or Body’s Beauty

Of Adam’s first wife, Lilith, it is told

(The witch he loved before the gift of Eve,)

That, ere the snake’s, her sweet tongue could deceive,

And her enchanted hair was the first gold.

And still she sits, young while the earth is old,

And, subtly of herself contemplative,

Draws men to watch the bright web she can weave,

Till heart and body and life are in its hold.

The rose and poppy are her flower; for where

Is he not found, O Lilith, whom shed scent

And soft-shed kisses and soft sleep shall snare?

Lo! as that youth’s eyes burned at thine, so went

Thy spell through him, and left his straight neck bent

And round his heart one strangling golden hair.

(Rossetti, Collected Works, 216)

(Fig. 5) http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/rossetti-proserpine-n05064

(Fig. 6) http://www.berkshirehistory.com/odds/briar_rose.html

References

[i] Hilton, Thomas, The Pre-Raphaelites (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1970), pp. 13-14

[ii] British Library, John Ruskin – Pre-Raphaelitism (2018) https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/pre-raphaelitism-by-john-ruskin

[iii] Gaunt, William, and John Bryson, “Gabriele Rossetti: Italian Scholar”, Encyclopedia Britannica (2018) https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gabriele-Rossetti

[iv] Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Poetry Foundation (2018) https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/dante-gabriel-rossetti

[v] Colville, Deborah, “Sass’s Drawing Academy”, UCL Bloomsbury Project (UCL, 2011) Available at: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/bloomsbury-project/institutions/sass_academy.htm

[vi] Riggs, Terry, “Sir John Everett Millais, Bt”, Tate: Art and Artists (1998) Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/sir-john-everett-millais-bt-379

[vii] Hilton, pp. 26-27

[viii] Riggs (1998)

[ix] Hilton, pp. 28-29.

[x] Ibid., p. 29

[xi] Ibid., p. 34

[xii] Ibid., pp. 49-51

[xiii] Ibid., pp. 74-77

[xiv] Marsh, Jan, Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood (London: Quartet Books Ltd., 1985), pp. 15-16

[xv] Ibid., pp. 16-17

[xvi] Hilton, p. 101

[xvii] Marsh, pp. 84-5, 87

[xviii] Marsh, Jan, and Pamela Gerrish Nunn, Women Artists and the Pre-Raphaelite Movement (London: Virago Press, 1989), p. 71

[xix] Ibid., p. 72

[xx] Cecil, David, Visionary and Dreamer – Two Poetic Painters: Samuel Palmer and Edward Burne-Jones (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1969), pp. 98-102

[xxi] Ibid., pp. 113-116

[xxii] MacCarthy, Fiona, “Burne-Jones’ Pursuit of Love” Oxford Today (2011) Available at: http://www.oxfordtoday.ox.ac.uk/features/burne-jones%E2%80%99-pursuit-love

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Cecil, pp. 128-9

[xxv] Ibid., p. 130

[xxvi] Williams, Isabelle, “Georgiana Burne-Jones and William Morris: A Subtle Influence” in The Journal of William Morris Studies (August 1996) pp. 17-18. Available at: http://www.morrissociety.org/JWMS/12.1Autumn1996/AU96.12.1.Williams.pdf

[xxvii] Morris, William, “Praise of My Lady”, The Defence of Guenevere (1858) Available at: https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/m/morris/william/defence-of-guenevere/chapter28.html

[xxviii] Fleming, R.S., “Victorian Feminine Ideal”, Kate Tattersall (2013) Available at: http://www.katetattersall.com/victorian-feminine-ideal-the-perfect-silhouette-hygiene-grooming-body-sculpting/

[xxix] Marsh, p. 120

[xxx] Ibid., pp. 125-6

[xxxi] Ibid., pp. 125, 129

[xxxii] Byatt, A. S., Peacock and Vine (New York: Knopf, 2016), pp. 14-15

[xxxiii] The Rossetti Archive, The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, Production Description (2008) Available at: http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/s40.rap.html

[xxxiv] British Library Online, Romantics and Victorians Collection (2014) Available at: https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/ecce-ancilla-domini-the-annunciation-by-dante-gabriel-rossetti

[xxxv] Marsh, p. 54

[xxxvi] Fowle, Frances, “Beata Beatrix”, Tate Gallery (2000) Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/rossetti-beata-beatrix-n01279

[xxxvii] Von Goethe, Johann Wolfgang, and Martin Greenberg, Faust: A Tragedy, Part One, p. 134. (Yale University Press, 1992). Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt32bwt3.4

[xxxviii] Rossetti, Dante Gabriel, “Lilith/Body’s Beauty”, in Swinburne, Notes on the Royal Academy Exhibition (1868)

[xxxix] Ibid.

[xl] Rossetti, Dante Gabriel, “70.110 Letter to Thomas Gordon Hake, April 1870” in William Evan Fredeman and Roger C. Lewis, The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The Chelsea years, 1863-1872, prelude to crisis : 1868-1870 (Samfundslitteratur, 2002), pp. 449-50

[xli] Berger, John, Ways of Seeing, in “A Life in Quotes: John Berger,” The Guardian (January 2002) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/jan/02/a-life-in-quotes-john-berger

.

[xlii] Byatt, p. 14

[xliii] Mazzarra, Federica, “Rossetti’s Letters: Intimate Desires and ‘Sister Arts’”, University College London Discovery (2008), p. 118. Available at: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/14104/1/14104.pdf

[xliv] Byatt, p. 11

[xlv] Landow, George P., “Pre-Raphaelites: An Introduction”, The Victorian Web (2015) Available at: http://www.victorianweb.org/painting/prb/1.html

[xlvi] “Andromeda,” Encyclopedia Britannica (2009) Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Andromeda-Greek-mythology

[xlvii] “The Romantic Period: Topics – The Gothic: Overview”, The Norton Anthology of English Literature, W. W. Norton and Company (2018) Available at: https://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/romantic/topic_2/welcome.htm

[xlviii] Marsh, p. 101

[xlix] Roe, Dinah, “The Pre-Raphaelites”, Discovering Literature: Romantics and Victorians (British Library, 2018) Available at: https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-pre-raphaelites

[l] Souter, Anna, and Rachel Funari “The Pre-Raphaelite Movement Movement Overview and Analysis”, TheArtStory.org (2018) http://www.theartstory.org/movement-pre-raphaelites.htm